Why We Hold Gold and Gold Stocks

May 5, 2025

Overview

In the current era of economic uncertainty, mounting US deficit, tariff effects, and geopolitical instability we maintain a position in gold and gold miners in our portfolios. We believe that gold serves as a critical hedge against all of these headwinds.

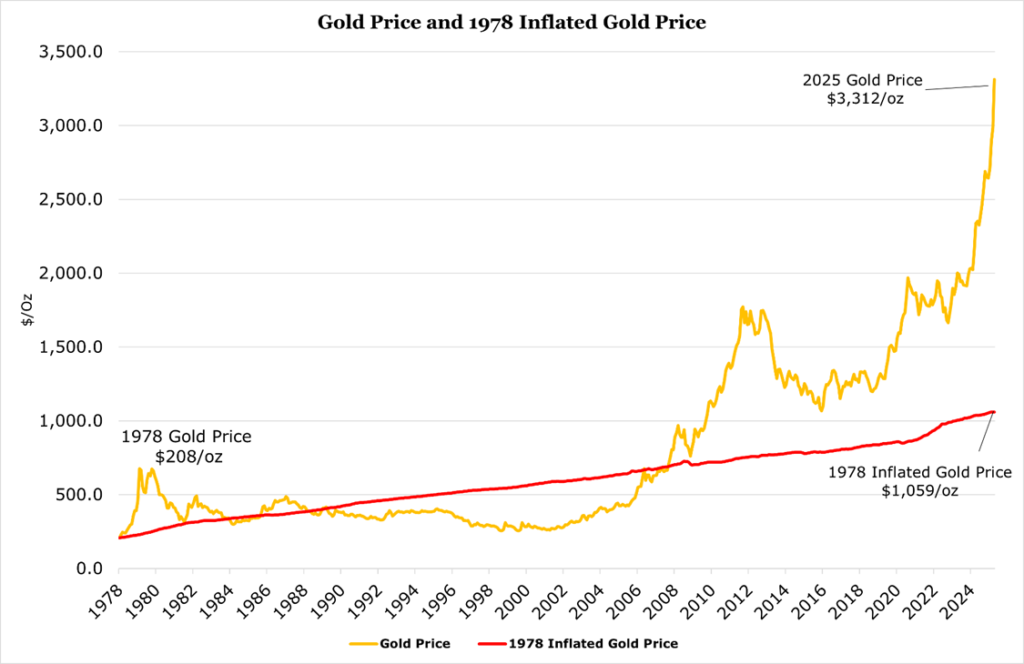

Unlike long-term bonds that suffer real-term erosion during inflationary periods, or equities vulnerable to margin compression from rising input costs, gold maintains its real value over time. Gold’s multi-millennia history as a store of value should not be viewed as mere tradition. We believe it reflects gold’s unique scarcity as an asset uncorrelated to government policy and immune to the debt spirals now threatening many developed economies.

A Brief History of Gold as Money

The idea behind metal backed paper goes back to the 17th century, when governments and merchants began issuing receipts against gold deposits to enhance the liquidity of trade. Over time, more certificates were issued than physical gold available, forming the earliest iteration of a fractional reserve banking system and providing credit to holders of physical gold. By the 19th century, central banks increasingly endorsed national reserves of gold-backed or gold-redeemable currency.

During WWI most major economies, especially in Europe, suspended the gold standard to finance their war efforts. After the war countries faced massive debts and inflationary pressures, leading to intense debates about how to return to a gold standard. European powers could not agree on a single system and some went back to the hard gold standard where anyone could exchange paper notes to gold, while others switched to a more flexible gold-exchange standard where only trade partners could exchange for gold.

The standout power was France. France had experienced hyperinflation in the early 1920s and chose to adopt a strict gold policy with high gold coverage and refused to expand domestic credit in response to rising reserves (a process known as sterilization). France’s conservative stance monetary policy attracted gold inflows and strengthened its currency. France’s stance also caused tensions with the US and Britain, who were in a period of monetary expansion. Though, the US also conducted sterilization policies during this time to offset its growing monetary supply which was fueling domestic speculation. These differing policies contributed to a fragile global system with unclear rules.

Between 1926 and 1932 monetary gold supply increased by 14%, which should have been more than enough to keep prices stable. However, due to the US and France conducting sterilization policies, benchmark inflation indices had fallen 35%.

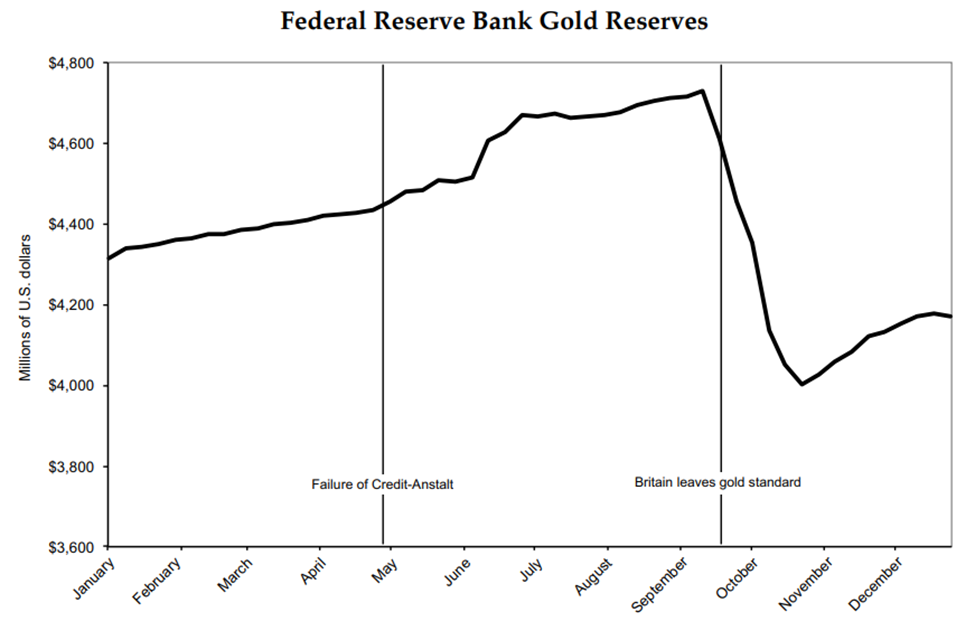

While most are familiar with consumer bank runs throughout the world during the early 30s, global trade was also shaken by panic. In 1931 the financial crisis blew wide open when Creditanstalt, a major Austrian bank, collapsed. This was followed shortly by panic spreading to German banks, then to the Bank of England, which all faced massive gold outflows.

Despite temporary credit support from the US and France, Britain was forced to abandon the gold standard in September 1931, triggering a domino effect as those heavily laden with Pounds or heavily dependent on British trade abandoned the standard within weeks. France and the ”Gold Bloc” (US, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland) attempted to stay on the gold standard a bit longer but suffered massive losses related to holdings in Pounds. In just the week following the Pound’s debasement, The Gold Bloc lost an estimated $33 billion in today’s money. Fearing larger economies would go off the standard, the Gold Bloc began to redeem gold where possible, with the US facing $15 billion in gold redemptions by the end of October 1931.

he political crisis deepened domestically during the 1932 election as President Hoover accused the Federal Reserve of planning to go off gold (which was untrue), warning that Roosevelt’s election would end the gold standard (which was, at the time, unplanned).

During the short few weeks when congress was not in session and the new president Roosevelt had not yet been inaugurated in early 1933, Americans redeemed an estimated $5.3 billion in gold certificates and runs on banks accelerated dramatically. Through deepening banking panic, the US formally suspended gold convertibility for individuals on April 5, 1933, through Executive Order 6102. While gold still backed the dollar in international transactions, the US permanently suspended domestic gold redemptions.

After WWII, the Bretton-Woods Agreement of 1944 sought to restore a more globalized gold-exchange system. It pegged the US dollar to gold at $35/oz, and all other global currencies to the dollar.

By the late 1960s, strain grew as US gold reserves dwindled amid growing fiscal deficits, trade imbalances and inflation. Bretton-Woods increasingly relied on trust in the convertibility of the US dollar rather than direct gold holdings. This caused uncertainty in the ability of the US to continue supplying gold redemptions. With fears of stagflation rising in the early 70s, it became evident to the Treasury that the US Dollar was overvalued compared to the gold backing it. In 1971, President Nixon unilaterally suspended dollar convertibility into gold, effectively ending the Bretton-Woods system and inaugurating the era of fiat currencies.

Modern Gold Markets

Modern gold is one of the largest asset classes in the world, estimated at $5 trillion, representing only 40% of the gold mined in history, with the rest being in jewelry, decoration, and other goods. The World Gold Council estimates that there is a total gold supply of approximately 210,000 tons across all uses, with the supply growing at a stable 2% per year. According to the US Geological Survey, there is 52,000 tons of proven gold reserves yet to be mined across the world.

Over the last 5 years, gold trading volumes have had a daily average volume of more than $150 billion per day, similar to 1-3 year Treasuries. However, only around 1% of global financial assets are invested in gold, or about $4 trillion in physical bullion and $1 trillion in derivatives.

| Use | % of Total Volume | Value |

| Jewelry | 46% | $6 Trillion |

| Central Banking | 17% | $2 Trillion |

| Investment Bars and Coins | 21% | $3 Trillion |

| Physically Backed Products (ETFs) | 2% | $0.2 Trillion |

| Industrial Applications, Private Holders | 15% | $2 trillion |

For trading bullion, there is an important distinction in how trades are settled. Fundamentally, unallocated gold, also called paper or pooled gold, is an IOU. Unallocated gold accounts represent a claim against the general holdings of an institution’s gold, making investors creditors. Allocated gold, also called fully reserved or pledged, represents a specific claim on an identifiable piece of gold that one legally owns and is legally distinct in the inventory of the holder.

According to the LBMA (London Bullion Market Association), above 90% of all gold traded on the LBMA spot market is unallocated. Given the LBMA is the largest settlement structure in the world for OTC gold trading, many other OTC markets such as Switzerland or OTC gold products offered through broker-dealers, operate on an unallocated structure. The OTC market is a black box, and regulations differ globally making reporting requirements, leverage, or stress testing difficult to specifically apply.

On the more regulated American futures exchange where most gold derivatives are traded, COMEX, more than 99% of the outstanding contracts are cash-settled or rolled forward, rather than physically delivered.

There are advantages to unallocated gold and cash-settled futures contracts. Paper gold is very liquid, has no storage and no transport costs, and allows for rapid price discovery. On paper, it also still allows the owner of the unallocated contract to request physical delivery of gold – though the contracts are typically very lenient, and the issuer retains the contractual right to refuse physical delivery in cases of “market disruption,” “liquidity constraints,” or “force majeure”.

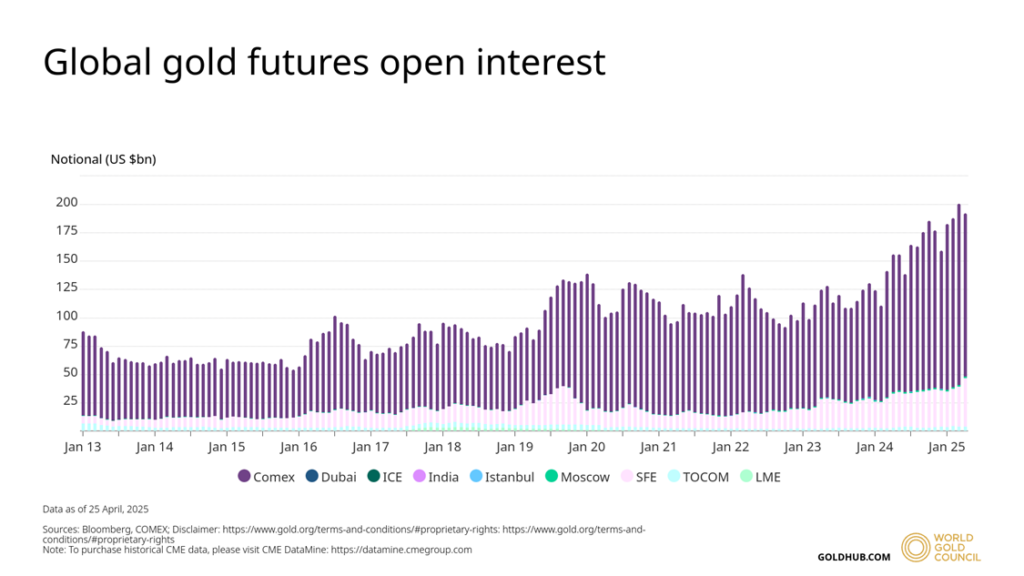

Most obviously the primary disadvantage to investors is that gold’s price has become separated from its physical scarcity. As previously mentioned on OTC markets, there is very little regulation or oversight on the level of leverage or how much paper gold is issued. For the quarter ending December 2024, LBMA averaged 50.15 million ounces in daily volume traded or about 40% of yearly mining volumes, or 18% of gold held in LBMA vaults, every single day. Determining the level of paper gold outstanding is an impossible task given the opaque nature of settlement, though there is likely at least a high amount of rehypothecation (reusing collateral to back multiple instruments). On the COMEX cash-settled market there is a daily open interest of around 45.86 million ounces against 21.45 million ounces of gold available for delivery in vaults.

Overall, gold as an investment has expanded substantially over the past few years, and has rapidly accelerated with tariff fears and renewed inflation expectations.

Basel III: A New Regulatory Wildcard

The Basel accords are intended to provide a regulatory floor for global banking to enhance stability. This manifests as setting capitalization requirements, conducting annual stress tests, and sets up scaffolding for risk management.

Basel III has added a new liquidity monitoring system, the NSFR (net stable funding ratio). NSFR was introduced to try to de-risk the inherent mismatch of maturities that have historically caused runs on otherwise perfectly capitalized banks. Under NSFR, assets and liabilities are assigned different RSF (required stable funding) levels, ranging from 0% to 100%, measuring what percentage of Tier-1 Capital must back each position. The best way to think of this is a “risk budget”, which theoretically adds another level of safety before banks begin to risk core capitalization.

| Description | Examples | |

| Tier 1 Capital | Core capital that absorbs losses | Common equity, retained earnings, convertible-to-equity instruments, bank cash |

| Tier 2 Capital | Supplementary capital that absorbs losses in insolvency | Subordinated debt, hybrid instruments, accounting reserves |

| Balance Sheet Asset | Owned resources used in business activities | Loans, bonds, real estate, gold |

| Balance Sheet Liability | Obligations the bank must meet | Client deposits, debt issuance, unallocated gold |

As it relates to gold, the treatment of unallocated gold positions has changed in a significant way that we believe will change the dynamics of the market. Prior to Basel III, unallocated gold was treated like any other balance sheet liability. However, for the purposes of stress testing, it was assigned a risk weight of zero meaning it was not considered a risky liability under capital adequacy rules. Primarily, unallocated gold’s treatment was locally dictated and as previously stated the local regulations were typically minimal or opaque-at-best.

The NSFR rule now assigns an 85% RSF factor to unallocated gold. Regulators see unallocated gold as inherently risky, equivalent to margin. However, allocated gold held by banks and physical gold held in vaults is assigned an RSF factor of 0%.

Already, issuers of unallocated gold have decreased the volume of positions and LBMA notes that it has the potential to raise costs enough to force some participants out of the market. The UK and EU market regulators have introduced applications to grant an exemption to certain components of the NSFR rule. However, the exemption is only granted if the bank can demonstrate that the assets and liabilities are linked. For gold, this means that unallocated gold issued without backing will still have the 85% RSF factor, and unallocated gold with sufficient gold backing will have a 0% RSF.

| Category | Allocated Gold (Pre-Basel III) | Allocated Gold (Basel III) | Unallocated Gold (Pre-Basel III) | Unallocated Gold (Basel III) |

| Capital Risk Weight (credit risk measurement) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Funding Treatment (NSFR RSF) | – | 0% RSF | – | 85% RSF |

| Trading Efficiency | Inefficient | Inefficient | Highly levered, low cost | Leverage constrained by funding cost |

| Operational / Custody Cost | High | High | Low | Medium, passing on costs to clients |

We believe the introduction of the NSFR rules does change the process for how investors choose to invest in long-term gold positions. We believe these regulatory changes will push investors toward allocated and physical bullion, as the NSFR mechanism dramatically increases the regulatory cost of issuing unallocated gold and gold derivatives not backed by physical gold.

The Deficit

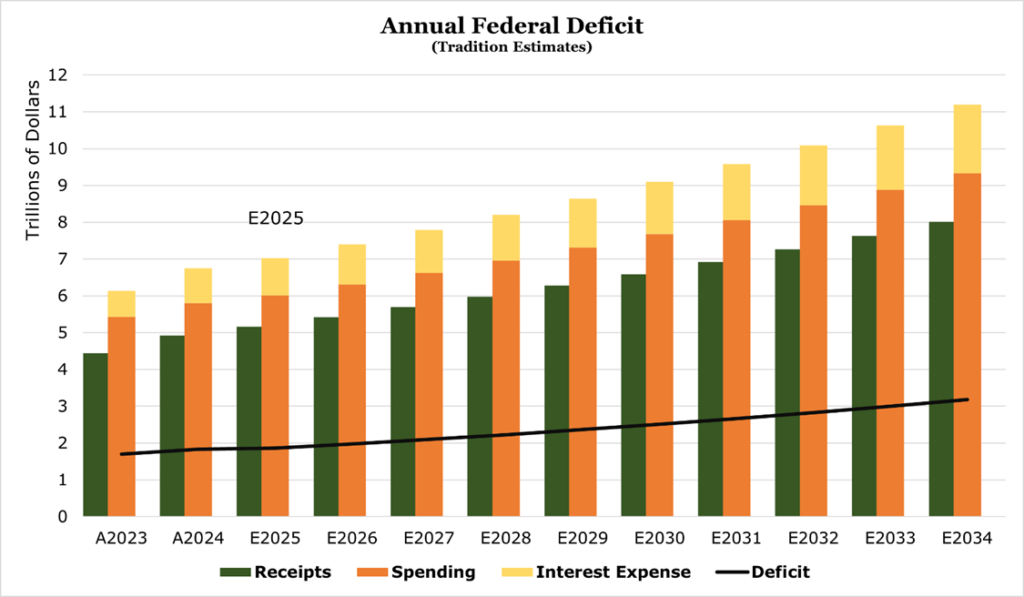

The United States has a debt problem, one we have talked about extensively and will only briefly discuss here. For a more detailed report, see our piece here, or our video here. During the fiscal year ending September 2024, the United States ran a $1.8 trillion deficit, or 6.4% of GDP. We project that the deficit for the fiscal year ending September 2025 will breach $1.9 trillion. This level of deficit spending, even for the largest and most powerful economy in the world, is not sustainable.

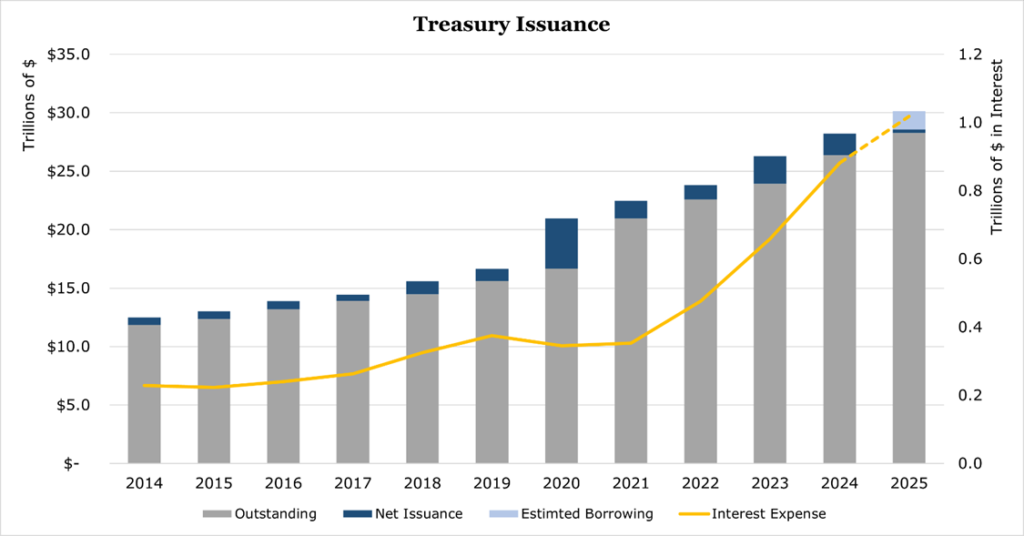

During 2025 interest payments will reach more than 3% of GDP, or around $1 trillion annually. This exceeds Medicare and defense spending, costing the taxpayer $2.6 billion every single day according to the CRFB. We have already entered the debt spiral; we cover our interest expense with more issuances which compound into more interest. Over the long-term the CBO now projects the terminal rate on all outstanding government debt will hit 3.6% by 2031, a 30bps increase compared to 2024 projections.

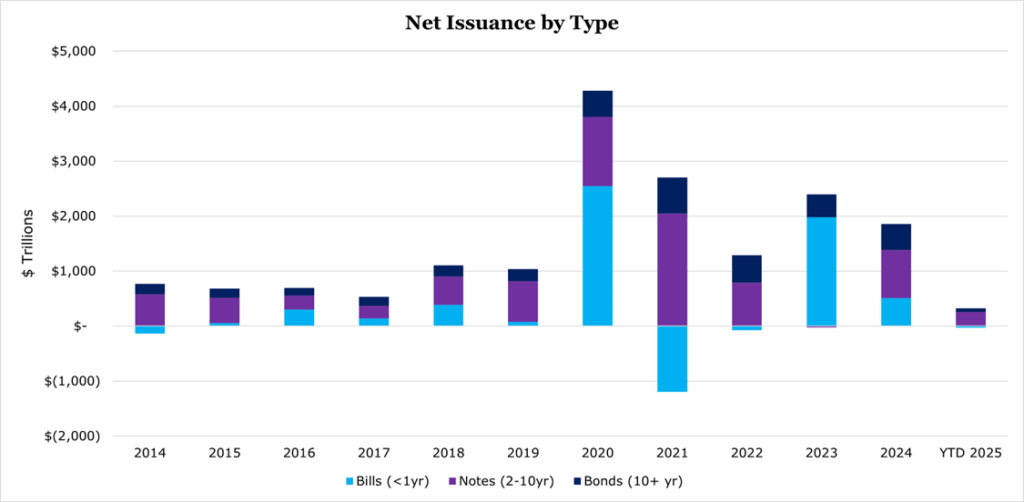

While this is mostly a fiscal responsibility problem, the Treasury department has attempted to skirt around issuing long-term debt under the high-interest rate environment, with the bulk of its issuances since rates began to rise in 2022 being shorter-term. There is now a massive rollover problem, with an estimated $3 trillion in short-term issuances that will need to be rolled over on top of $2 trillion in new issuance.

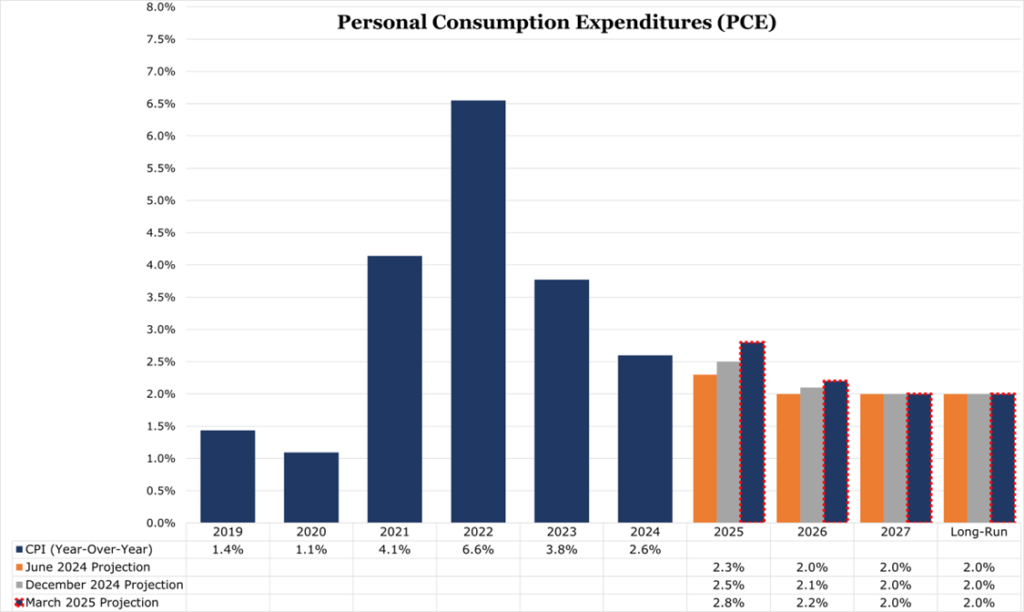

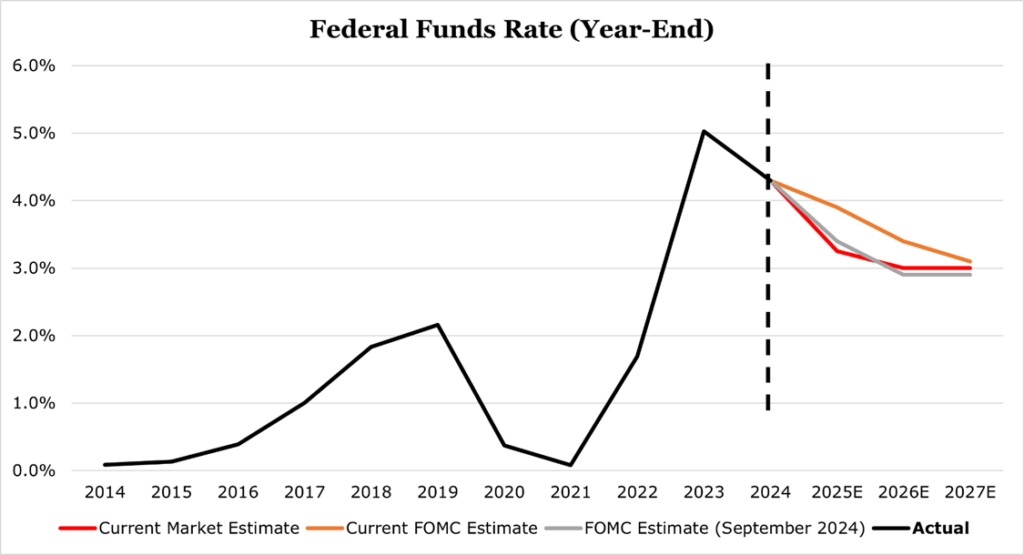

Combined, the FOMC has raised its inflation expectations to 2.8% for 2025. This means they expect inflation to re-accelerate during the year. It is important to note that their projections were made before the unilateral tariff announcements.

The Fed

There are very few viable options to fixing the debt problem. Given the lack of political will to tackle entitlement reform, reign in spending beyond symbolic gestures, or raise taxes, we believe that the US government is going to pursue a policy of monetizing the debt. Numerous members within the Trump admin, including Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, have advocated for a weaker dollar. Additionally, there have been reports of efforts to oust Jerome Powell, although denied, over his refusal to push the FOMC to lower rates.

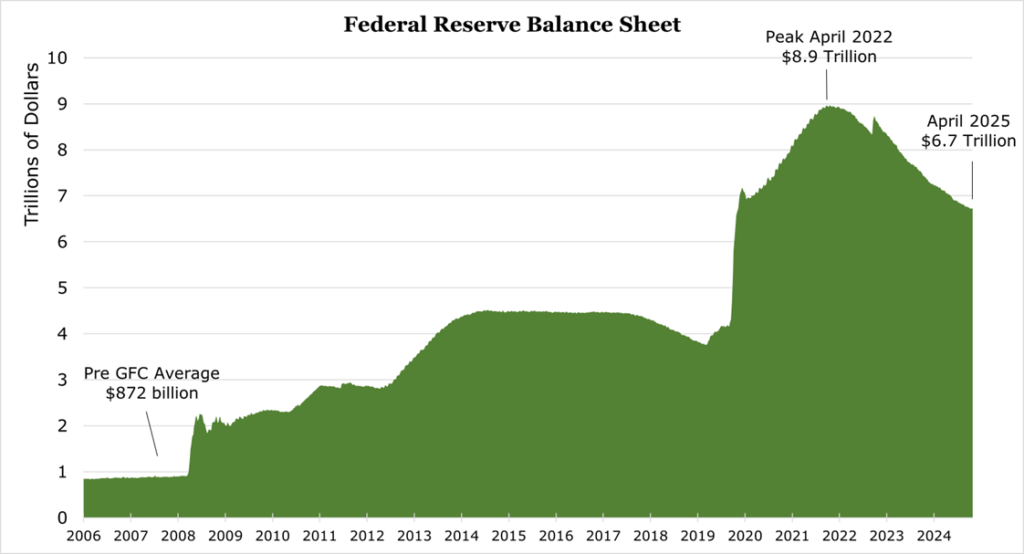

Both of these political factors signal that monetary tools are on the table for fiscal objectives. The Fed’s dual mandate does not include financing the government or controlling the yield curve to support excess deficit spending. However, we have likely passed the point of fiscal dominance, over the last 20 years the money-for-nothing QE has certainly not deterred the government from thinking the gravy train would run forever.

When implemented in a controlled, targeted way, QE expands the monetary base during downturns by buying Treasuries, which also lowers long-term rates, and helps sustain consumer demand. Combined, these measures soften the severity and duration of recessions. As discussed in the historical section, economic downturn coupled with deflation can extend recessions into depressions.

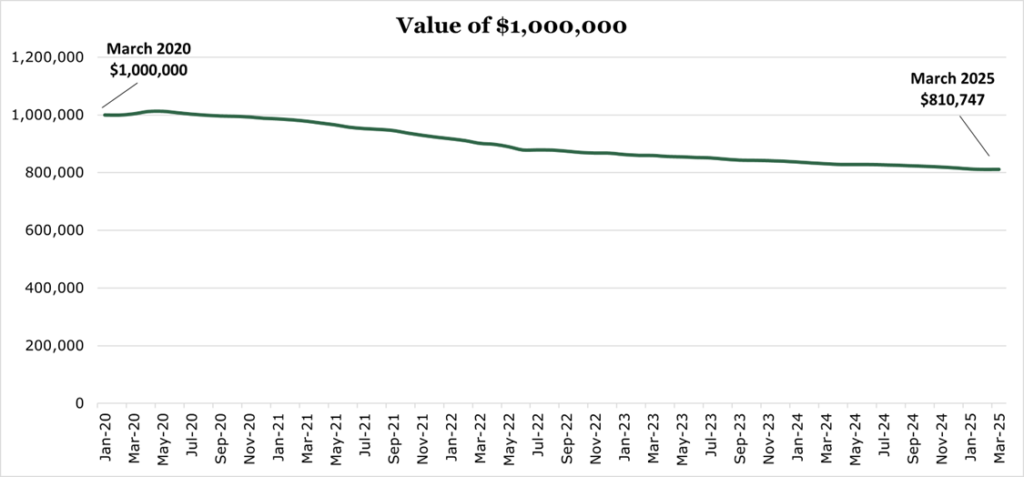

However, when used over the long-term, QE results in a weaker dollar, higher inflation, and sustains government deficits. Not only does this erode the effectiveness of the Fed’s own monetary policy tools in the long term, but it also erodes the real value of outstanding debt and destroys individual spending power.

The underlying calculus suggests that if America can simultaneously reduce its interest burden, gain export advantages through currency effects by monetizing the debt, and simultaneously rebuild its industrial base, the resulting growth might eventually outpace debt accumulation.

In the absence of political appetite for tax reform, or entitlement restructuring, it has become the only politically palatable path. It is also the path the most destructive to the spending power of individuals.

Trade Policy

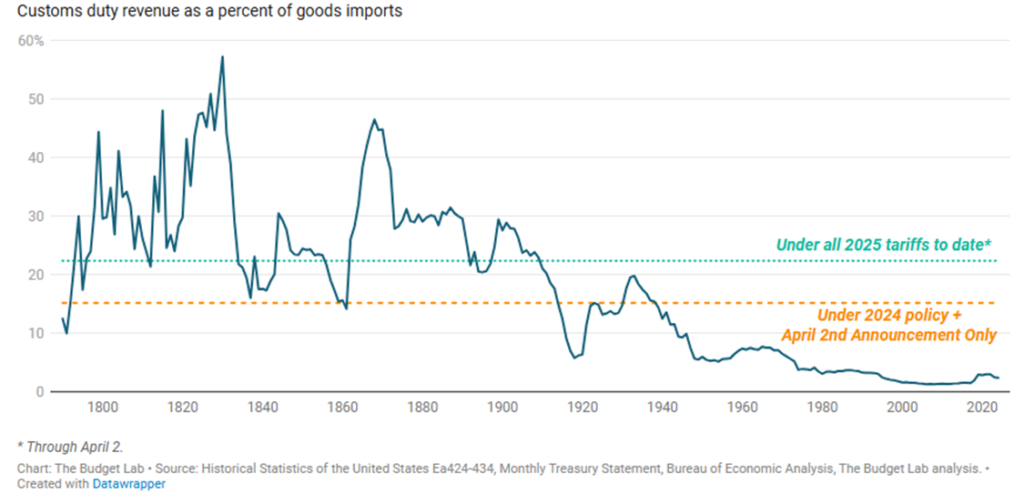

Proposed universal tariffs, in theory, are being levied in order to reduce American reliance on imports, generate tax revenue to offset massive tax cuts, and reshore American manufacturing. Though there is a contradiction, while domestically pursuing policies that would weaken the dollar, the tariffs would artificially increase the value of the dollar.

Theoretically, the argument for tariffs is the belief that American manufacturing can be revived by shielding domestic firms from foreign competition where there are substantial competitive advantages in resources or labor like in China, Vietnam, or Mexico. By imposing broad tariffs, policymakers can reduce the appeal of cheaper foreign goods, create a more predictable investment climate for domestic producers, and encourage the return of industrial capacity to the US.

In a vacuum it might work. In reality, other countries will retaliate with their own tariffs on US imports or weaken their currency ahead of the USD to mitigate the effects of tariffs. Combined, these things will drastically increase the prices of inputs that cannot be produced at scale domestically, like aluminum, steel, specialized machine tools, or platinum group metals. Additionally, domestic producers now shielded from competition, gain high amounts of pricing power and face fewer incentives to operate efficiently as they can pass on costs to consumers.

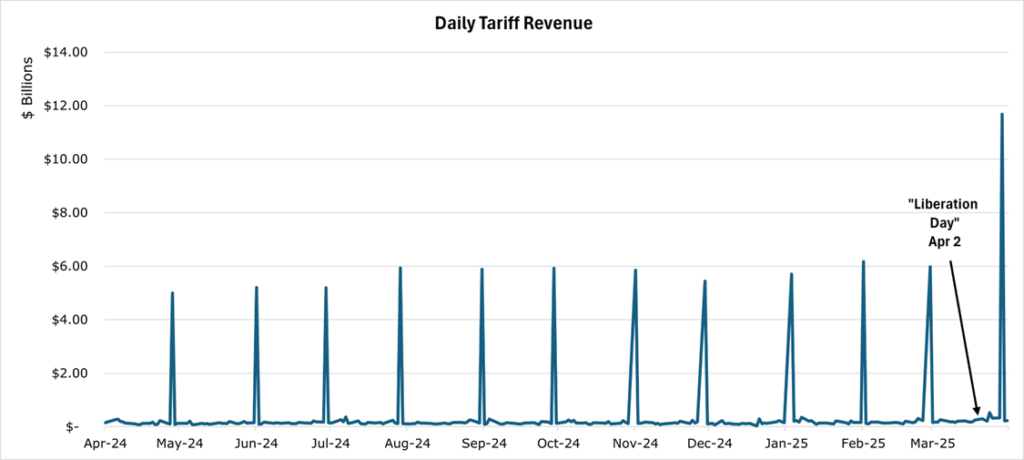

According to the DHS, the Treasury is making $15.67 billion per month on tariffs and annualized at $188 billion. Not even considering the economic impacts of retaliation on the tax base or the increase in prices, this is only enough to run the government for 9 days per year. As importers adjust, this tariff revenue is likely to decline; hence, we think tariff revenue will be immaterial to helping solve the deficit problem.

Effective trade interventions require clear objectives and consistency of enforcement. Businesses depend on long-term expectations to make investment decisions, and if objectives and enforcement are changing by the week, it does not matter how much revenue the tariffs are bringing in.

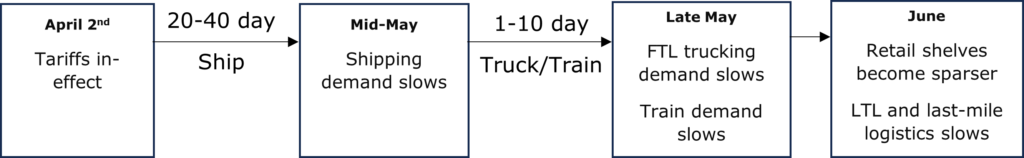

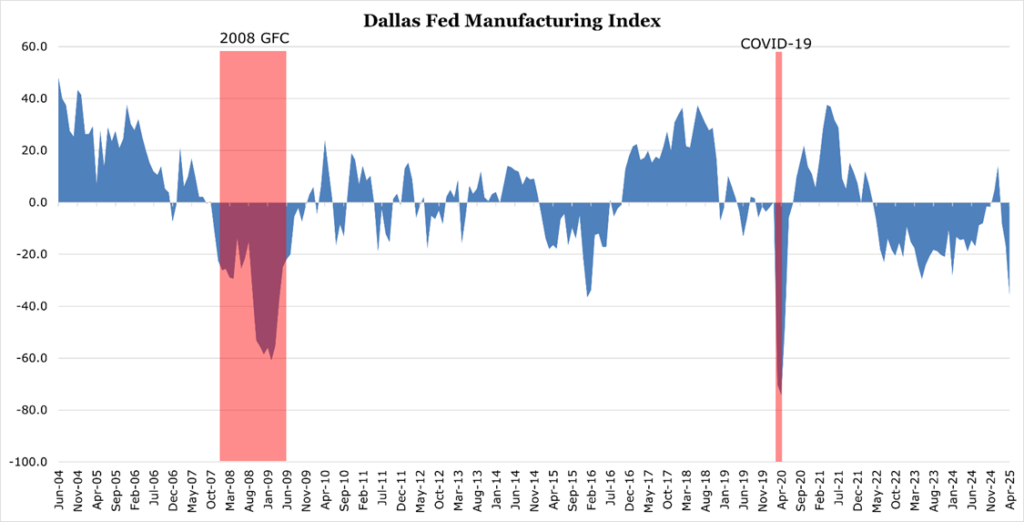

When tariff rates and targets appear arbitrary, official messaging lacks consistency, and the introduction is sudden, the result is deep uncertainty. The Yale Budget Lab estimates that long-run real GDP will contract by 0.56%, and inflation will rise 2.3%. We believe over the short run these tariffs have increased the possibility of an economic recession and could increase inflation as well. Uncertainty causes business leaders to get more conservative which means they expand and invest less, while managing employment through fewer hirers and more work force reduction.

International Consequences

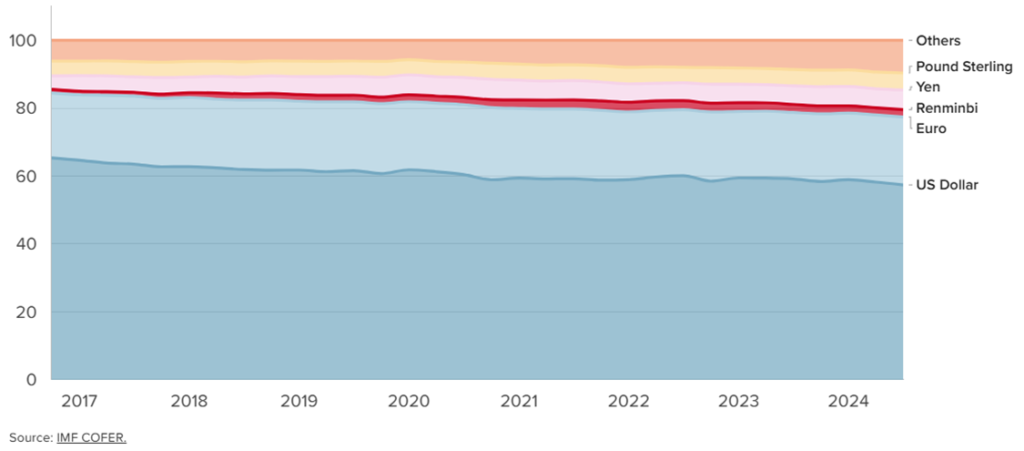

We’ve discussed international de-dollarization on two separate articles, here and here. To recap, there are several secular factors that have contributed to a broad central bank shift away from US Dollars, especially in the developing world.

Firstly, the global fear of inflation and broad tariff disruptions have moderated growth expectations while increasing inflation expectations. In Europe, tariff fears had inflation expectations creep back up to 2.8%, though consumer sentiment remains stable. Japan, one of the US’s key trading partners, has had inflation expectations spike to 9.6%, the highest level since 2006. Consumer sentiment fell to -59.9, the lowest since December 2022.

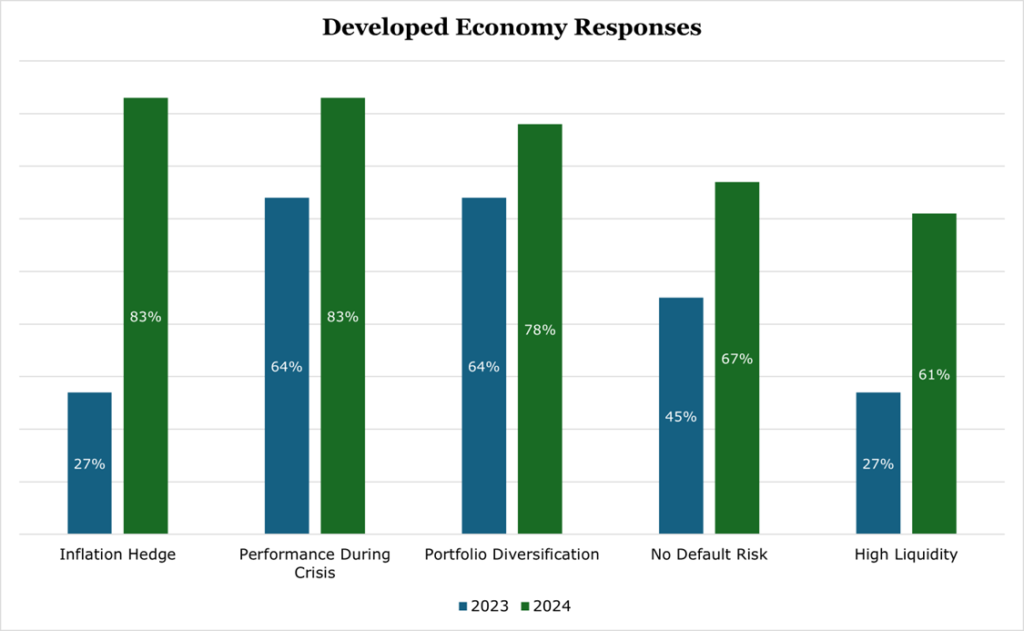

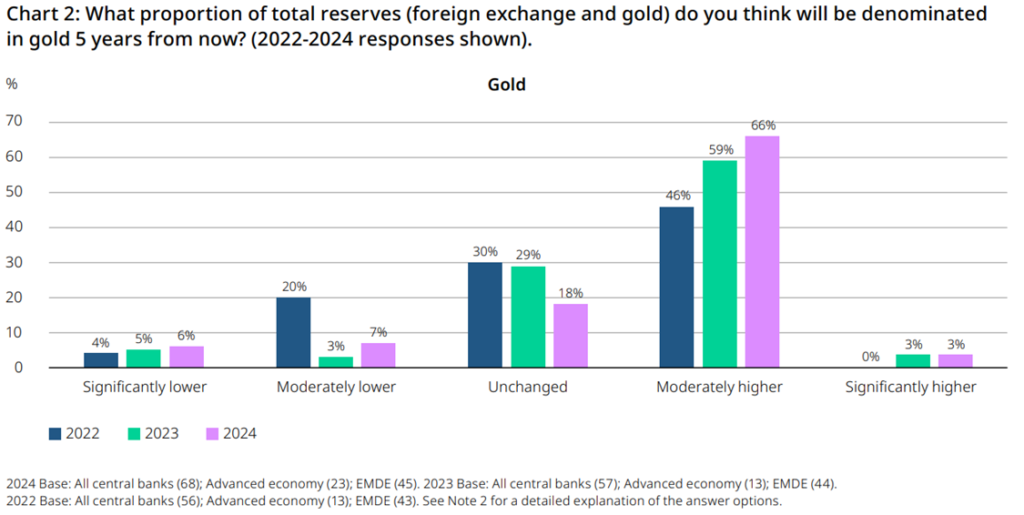

The 2024 Central Bank survey, conducted by the World Gold Council in June 2024, saw a single across-the-board change: developed economy central banks are now holding gold for strategic reasons. Even pre-tariffs, global inflation staying sticky has seen the belief that gold is a valuable inflation hedge return to the forefront of strategy.

This change in strategic thinking in our view will see the amount of USD used in cross trade decreasing secularly even if tariffs are reversed.

Secondly, relative strength of the US dollar over the last 5 years has had an outsized impact on weaker currencies. Around 88% of Forex transactions on a yearly basis are conducted in US Dollars. Everywhere except Europe, the US Dollar has a dominant share in export invoicing. This means that countries need to exchange their local currency to or from USD. US Dollars account for roughly 51% of central bank reserves and roughly 60% of all global banking deposits and loans. When the US dollar dramatically strengthened against global currencies in the aftermath of COVID-19 it eroded the purchasing power of other currencies, compounded by global inflation. Conversely, now that the dollar is weakening, the reserves that were held are now worth much less which has driven foreign exchange holdings of the USD to multi decade lows.

Finally, shutting Russia out of SWIFT and unilaterally seizing or freezing assets has demonstrated that access to the global financial system is conditional on Western support. Countries on a less-than-friendly footing with the US or Europe like Iran, Russia, or China have begun to settle trade in other currencies or even in Gold. In the 2024 Central Bank survey, 68% of developing market economies reported they held gold because of concern over systemic financial risks, 42% of reported one of the reasons they were increasing their gold reserve levels due to a shift in global economic power and 26% responded they were concerned about sanctions.

Conclusion

Domestically, over the short term the weak dollar and high tariffs will most likely cause an uptick in inflation which drops consumer spending power. Over the medium term, some companies may relocate production if messaging improves, but inflation will persist due to the higher costs of domestic production and continued high cost of importing inputs or shortfalls of goods. Over the long term, it is possible prices will stabilize but will certainly not deflate given the continued deficit. Internationally, not only is the US now seen as a potentially unreliable partner, but the continued weaponization of western financial architecture has taken its toll.

Unlike long-term bonds that deteriorate in real terms, or equities vulnerable to margin compression from higher input costs, gold maintains its purchasing power over time. Often, gold outperforms during periods of economic uncertainty and during periods of higher inflation. We believe that combined all of these factors will favor investments backed by physical gold and investments in quality miners.